fax (000) 000-0000

fax (000) 000-0000

toll-free (000) 000-0000

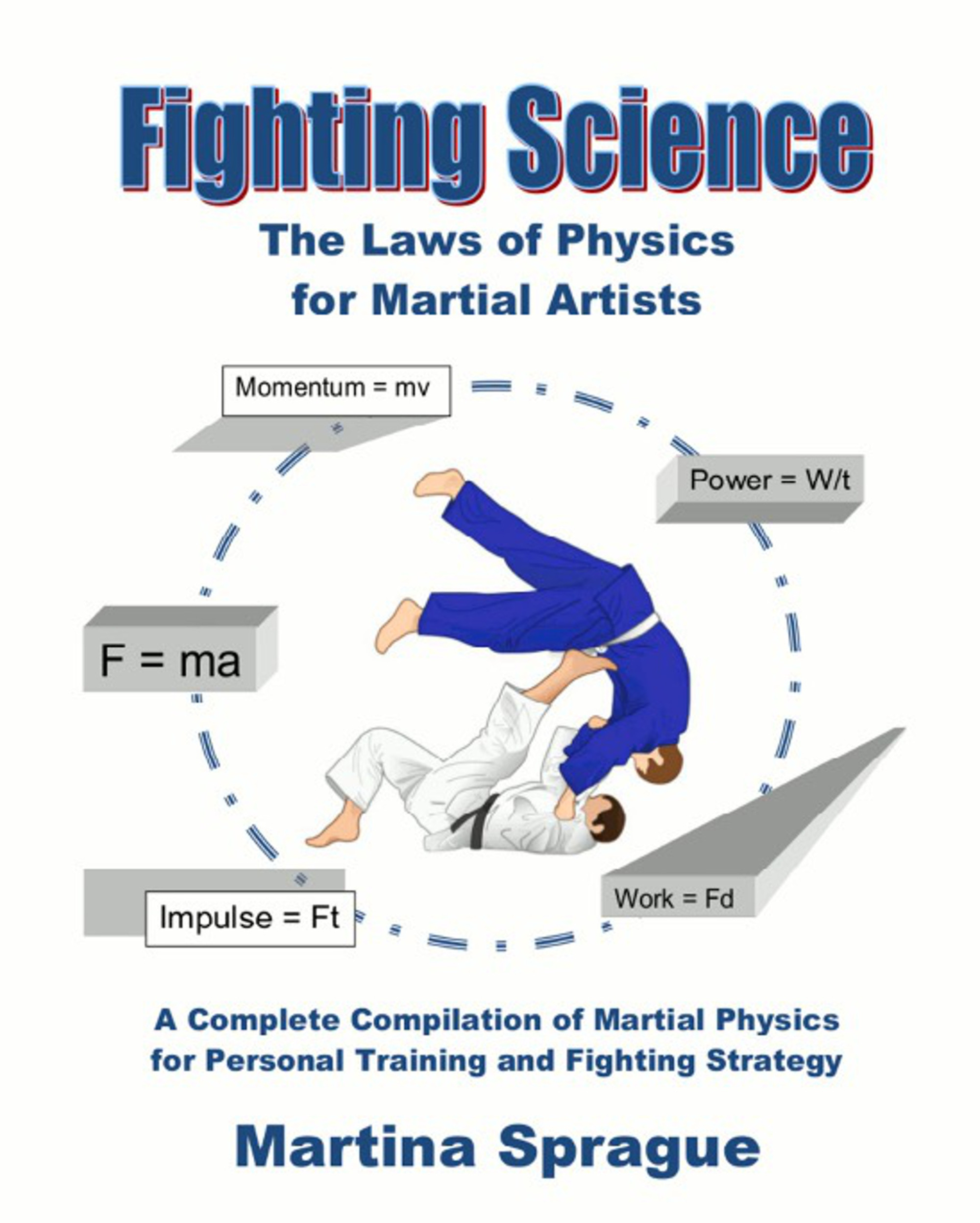

Fighting Science: The Laws of Physics for Martial Artists

You hate physics? You're just not a math whiz?

Many of us squirm when we hear the word

physics, and the first

that comes to mind are numbers and letters mixed into a sort of

incomprehensible language called equations. But don't worry.

The physics we will discuss here is conceptual physics, which relies

primarily on concepts rather than equations. Concepts are ideas with

which we are already familiar. These ideas are then related to the

martial arts (power, in particular). Below is a list of the few

equations you need to know and their commons symbols. These are

explained in detail throughout the text:

1. Momentum = mass X velocity (p = mv)

2. Force = mass X acceleration (F = ma)

3. Torque = force X lever arm (T = Fr)

4. Impulse = force X time (j = Ft)

5. Work = force X distance (W = Fd)

6. Power = work / time (P = W/t)

7. Kinetic energy = 1/2

mass X velocity squared (K = 1/2mv2)

Although many books about power in the martial

arts rely on physical conditioning and prompt us to do pushups and

situps and plyometric exercises, this book takes us through the back

door and shows us the

principles of physics behind power. The purpose is not to

negate the importance of physical conditioning, but to complement it

by broadening our understanding of sound mechanics of technique

through the use of the natural laws of motion. It thus takes us to

the highest stage of learning (correlation) through the laws of

physics. The first chapter compares standup fighting (karate,

kickboxing) and ground fighting (grappling), and explores how the

concepts of physics and strategy apply to both. Subsequent chapters

discuss and define the terms and concepts in detail, breaking them

down into their component parts. We will then train using the laws

of physics to our advantage.

Before gaining proficiency, however, we must

learn proper mechanics of technique. This is called mechanical

or rote learning, and is memorization without understanding. The

mechanical stage does little good in free sparring, yet is necessary

as a foundation for continued growth. The second stage of learning

is called understanding. When reaching this level, we know

when to do a technique and why the moves follow a particular

sequence. We can now answer questions about the technique, without

necessarily being proficient in its execution. The third stage of

learning is called application. We can now use what we have

learned in unrehearsed sparring. The fourth stage of learning is

called correlation. This is where the concepts of one

technique are applied to another, or where the concepts of standup

fighting are applied to grappling, and vice versa. Providing that we

have learned sound mechanics of technique, our knowledge and skill

from one style of martial art will now carry over to another,

allowing us to diversify our skill without spending years perfecting

a particular martial art. We can now become our own instructor.

Once we understand the principles that apply to

balance, body mass in motion, inertia, direction, rotational speed,

friction, torque, impulse, and kinetic energy, the need to memorize

hundreds of techniques vanishes. A true principle applies to all

techniques and all people, whether we are standing, sitting,

kneeling, prone, or supine; whether we are big or small, strong or

weak. Physics is neither good nor bad; it can neither be given to us

nor taken away. It applies equally to all people at all times. It's

how we use it that makes the difference.

As you proceed, keep in mind that certain words that have an exact meaning in physics have occasionally been used in everyday language. An example is the word power. In physics, power is defined as work/time. But to the martial artist, the term power can have diverse meanings and is commonly used to determine how much damage we can do when landing a strike or kick. The way the martial artist uses the word might prove disturbing to the student of physics. But since the book is written for the student of martial arts, power should primarily be thought of as the force of impact of a punch or kick. A student of physics might also frown on the fact that we have chosen to display numbers without specifying units. This is done to simplify the text and retain focus on concepts rather than equations. To ask a student of martial arts to strike with a force of a certain number of newtons, would have meaning only if he or she had some prior knowledge of physics.